by Verne R. Albright

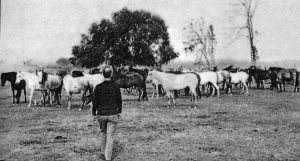

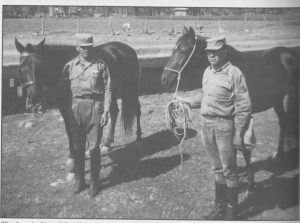

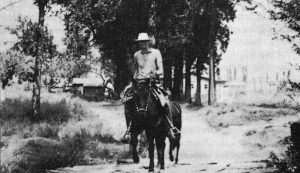

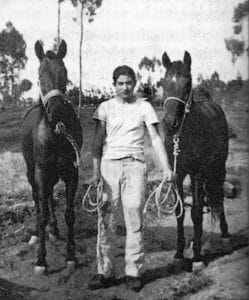

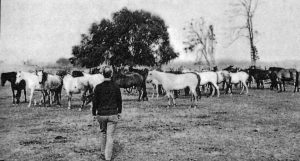

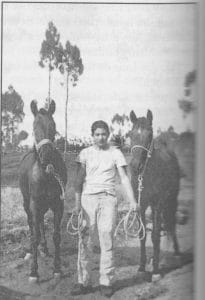

During nine months in 1966-1967 Verne R. Albright traveled overland from Peru to California with two Peruvian Paso mares: Ima Sumac from Hacienda Pucala and Hamaca from Casa Grande. The trio travelled 8,000 miles, 2,000 on foot and the rest in vehicles, including trucks, trains, and airplanes. Full of hardship, challenge, and adventure, their journey called attention to the Peruvian Paso breed and was the subject of a best seller,The Long Way to Los Gatos. Afterward Verne embarked on a mission to promote and preserve this special breed. Back then there were less Peruvian Pasos than there were bald eagles, which were on the Endangered Species List.

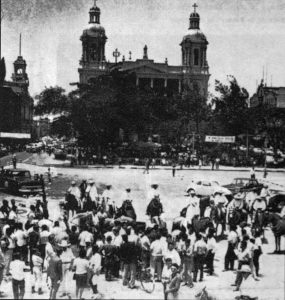

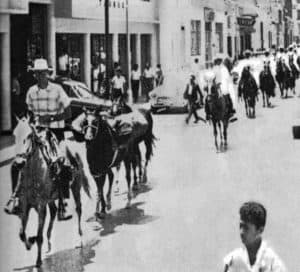

Peru’s newspapers were full of stories about my proposed ride from Peru to California because I was using their country’s National Horse, the Peruvian Paso. On the day I set out, the town of Chiclayo saw me off with a parade. People who came to wish me good luck filled the streets and Plaza Central. At a reception, the mayor gave me a letter for his counterpart in Los Gatos, California, my destination. The Catholic Bishop blessed my enterprise. A representative of the national Paso horse association in Lima presented me with a scroll to officialize my ride.

On the outskirts of town the police motorcycle escort turned back. Twenty-two riders from nearby haciendas had also accompanied me. I stopped my horses and faced them. One-by one they rode up and shook my hand, their serious expressions emphasizing the enormity of my task. More than Chiclayo’s mayor, Bishop, or leading citizens, they understood the difficulties I’d face. After somber good-byes they led their horses toward waiting trucks, and I rode into the desert.

Whenever I was near the Pan-American Highway, people parked their cars to talk and busses passed with passengers applauding. Drivers stopped their soft drink trucks and gave me free refreshments. In towns, merchants refused payment for what I brought to their cash registers. Along the trail, newspaper photographers appeared out of nowhere, asking questions and taking notes. A photographer showed up in the desert, riding cross country on a bicycle. Reporters waited at the entrance to towns, checking their watches as if recording an historical event.

And at the end of each day, people competed for the honor of hosting me and my horses. It was heady stuff, but Peru’s extraordinary kindness only briefly delayed my rendezvous with reality. Soon I was in terrain so rugged that my horses’ hooves were honeycombed with nail holes because their iron horseshoes had to be replaced every other week.

I had years of experience with horses but much to learn. After passing bloated, dead mules, I learned to recognize toxic plants and poisonous snakes. In Andean valleys, farmers taught me to weave sabila plants into my horses’ manes to ward off vampire bats. In deserts so hot the sand burned my feet right through my boot soles, I figured out how to find water with my wallet rather than a divining rod. Some nights I spent hours filling my horse’s water buckets at remote wells…or buying a glassful at a time from people who could only spare that much.

There was no happy medium. I stated in a desert but was soon shivering in a land of volcanoes, glaciers, and Andean peaks that dwarfed the highest in the Rocky Mountains. Soon I’d sweat in the tropics and in more deserts, one 113 feet below sea level. In desperate times I dined on goat jaw or guinea pig and my horses ate bananas, coconut, sugar cane, flour, and corn stalks.

Along the way, I met smugglers, a famous bullfighter, a witch doctor, a camera crew from ABC’s Wide World of Sports, a bullying small town sheriff, a snake hunter, a road grader driver who did his best to run me down, and a beautiful American girl named Emily. I navigated around natural obstacles and corrupt officials, but flew over Colombia to avoid bandit gangs ravaging that unfortunate country.

People frequently traipsed after me, hoping to start conversations. They were usually polite enough to require acknowledgement before approaching. But as I passed through a town in Ecuador’s Andes, I was followed by a man on a mule. He was soon was joined by five similarly mounted companions in dirty suits and various stages of inebriation. Moving my horses into a faster walk, I started looking for an army post or police station.

At the city limits, I wondered if I should continue into the unpopulated area ahead. But what other option did I have? If I stopped I’d be surrounded. If I turned back to town, the group behind me would be joined by more drunks. Beyond town the leader put his mule in a trot and came alongside me.

“I’m the law in the town you just left,” he announced. “You’ll have to show me your passport and the contents of your bags.”

“Do you have anything to show you’re the law?” I looked at him without slowing down.

“I’m not making requests! I’m giving orders,” he replied sternly.

“How do I know you have the right to do that?”

“Señor, you must stop at once!”

“As soon as I see a badge or some other proof of your authority.”

We were at a temporary stalemate. Obviously the law didn’t have a badge. And I wasn’t about to be talked off my horse. Besides, I was pretty sure his deputies would abandon their mission if it proved difficult. But their leader repeatedly ordered me to stop and dismount. I stayed ahead of his mule and double-talked him, hoping he’d give up. Instead, he abruptly jumped his mule between my horses and grabbed Ima Sumac’s lead rope. Holding its other end, I whirled Hamaca toward him.

“I’ll show you my passport and baggage if you show me a badge.” I said, hoping he’d take one out of his pocket. Another stalemate, but his deputies were now surrounding me. I survived this run-in, but only after a high speed chase that ended when a man in a road grader came within inches of running me down.

Future adventures would include a revolution in Nicaragua and becoming a fugitive from the law in Mexico. But I’m getting ahead of myself….

Central America’s policemen seemed to think I was a CIA agent on a covert mission. Their suspiciousness was an unsettling contrast to Peru where I’d been assisted many times by policemen. Back then, my horses had been sleek and well-groomed—objects of admiration and compliments. Now their dull coats were faded by sweat and the searing tropical sun.

Central America’s muggy air was saturated and could absorb no more moisture. My clothes were still wet with perspiration when I put them on in the mornings. Thanks to insect bites, Hamaca’s and Ima Sumac’s hair fell out in chunks. I bathed them with disinfectant and sprayed them with repellent. At night, they slept standing next to smoldering fires in smoke that irritated their eyes but kept disease-carrying insects at bay. I had to submerge their hay in water long enough to force ticks to let go and float to the surface where I terminated them with extreme prejudice.

Days before reaching San Jose, Costa Rica, I met an American who’d deserted rather than fight in Vietnam. He predicted I’d meet a beautiful woman in Costa Rica’s capital and was absolutely right. I wonder if Emily would have seemed as beautiful if I hadn’t been deprived of female company for so long. I think so. She was the sort of woman I liked and always had.

She and I went horseback riding and enjoyed an evening at the movies before I left. By the time I reached Managua, Nicaragua, I missed her so much I took a bus back to Costa Rica. We had a chaperoned dinner where she told me she’d attend a Guatemala City conference in a week, then suggested I put my horses in a gallop and meet her there.

I hitchhiked at top speed—horses and all—across four nations, hoping to see Emily again. The lowest moment came when a Honduran border official charged me an outrageous sum for a submachine-gun-toting soldier who rode in the back of the truck with my horses to prevent me from selling them without paying taxes.

My reward for days of effort was to see Emily for an hour downtown, two hours in a park, and a quick good bye at the airport when she returned to Costa Rica. After she left, I sat alone and lonely on the airport roof—unaware one of the planes that landed was hers, returning with engine trouble. We could have spent an entire day together if either had known the other was still in Guatemala City.

In Central America’s tropical climate, life was abundant and showed up unexpectedly. Tiny, mysterious creatures swam in puddles shortly after rainwater collected. Having come from who-knows-where, they swam until the water evaporated and were seen no more. Flying insects near Lake Nicaragua were so thick I couldn’t breathe without inhaling them. Disease-carrying organisms were equally plentiful. Ranchers refused me access to their property until Hamaca and Ima Sumac were bathed in a caustic solution. It killed hoof and mouth virus and also blistered their skin, causing patches of hair to fall out. One morning anthrax was reported a few miles from where I’d spent the night.

Among Andean Indians, tuberculosis was epidemic and malaria common. For days I’d been uneasy about these and other health hazards. In every town since entering Ecuador I’d seen posters recommending malaria shots. In Loja, the first large city, I went to the local Peace Corps office and spoke with a North American nurse.

“I’m not authorized to treat or give medical advice to Americans,” she said crisply. “I can work only with the local poor.”

“Can you recommend a doctor?” I asked.

“We’re not allowed to do that,” the nurse replied in the same tone, “and to tell the truth, there are few I could recommend in good conscience.”

I thanked her for her time and turned to go.

“Why are you in Loja?” she asked.

“I’m going to the States on horseback.”

“Oh, God! You have no idea of the diseases they have here. What are you doing for food?”

“Buying it where I can.”

“Listen, I’ll give you a gamma globulin shot for protection against hepatitis,” she volunteered. “I’d also advise you to take precautions against malaria, typhoid, tuberculosis and bubonic plague. Do you read Spanish?”

“Yes.”

“Here’s a pamphlet that tells you how to avoid cholera.”

Though tuberculosis was a terrible disease, I was accustomed to hearing about it. But typhoid! Malaria! Cholera! Bubonic plague! I thought they’d been banished to history books and horror stories.

One of my early hosts had been Peru’s richest man. Now I was enjoying the equally generous hospitality of the poorest yet kindest people I’d ever met. As a result, my horses shared quarters with pigs, deer, sheep, cows, chickens, llamas and—in one instance–convicts. I slept in tool sheds, chicken coops, feed troughs, and empty jail cells.

I finally reached Mexico, the last country between me and home. There a border official harshly advised that I’d have to pay a deposit or ship my horses to California by train. If I had admitted I couldn’t afford either alternative—which I couldn’t—I’d have been denied entry.

In contrast to the Guatemalan side, it took twenty-four hours to meet Mexico’s requirements. It was the lengthiest, most complicated, most expensive border crossing yet. First the customs inspector had me unpack my duffel bags. It took two hours to untie, unload, unlock, unpack, and spread out my worldly goods for him. Advised that all was ready, he announced that the inspection wouldn’t be necessary after all. I almost demanded it, fearing another change of heart after everything was repacked.

Next, the official veterinarian was summoned from Tapachula, twenty-five miles north. It took him most of the day to arrive, glance at my mares, fill out a form, and charge me a hefty fee for services and travel expenses. Then the customs official demanded a deposit to guarantee I wouldn’t sell my horses in Mexico. I didn’t have that much money but had gotten around the same requirement in Panama by having officials mark my passport so I couldn’t leave without my mares. I showed my passport’s Panamanian visa stamp to prove it.

“This is Mexico!” the official barked. “We don’t care what they do in Panama, or anywhere else!”

It had been my intention to next show my letters of recommendation from Costa Rica’s and Guatemala’s Secretaries of Agriculture. Suddenly that seemed like a bad idea. After much back and forth, I understood why stalemates are called Mexican standoffs. Next I was referred to the man in charge. Hard of hearing he was also unbendable.

“My job is to enforce the law and that I must do,” the jefe announced, tiring of my persistence. “You can pay the required deposits or get out of Mexico.”

Admitting I didn’t have enough money would have made me a potential vagrant.

“Please señor,” I pleaded. “Is there no way I can cross Mexico without deposits.”

“There’s one,” the jefe said. “You can ship your horses to California by train on the condition that you don’t unload them at any time.”

I walked to the train station and purchased passage to Mexico City for myself and two mares. When asked for the cheapest possible fare, a very cooperative agent discovered a technicality under which I could send my mares express for less than it cost to ship livestock.

“If you take your horses off the train for even an instant, they’ll be confiscated, and you won’t be allowed to appeal for their return,” the jefe warned as I led my mares toward the train.

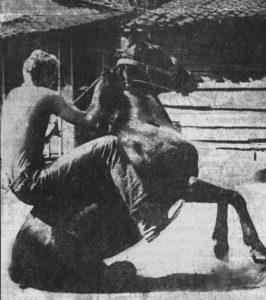

I took them up a slipper y polished steel ramp and tied them among packages and crates destined in the express car. Intending to ride with them, I was ordered out of the car by the man in charge. He had second thoughts when Hamaca and Ima—like oversize beavers—began reducing a wooden crate to splinters.

y polished steel ramp and tied them among packages and crates destined in the express car. Intending to ride with them, I was ordered out of the car by the man in charge. He had second thoughts when Hamaca and Ima—like oversize beavers—began reducing a wooden crate to splinters.

That night at Mexico City’s railway depot I lay on a freight cart in a warehouse. Planning what I had to do in the morning kept me awake all night. I was about to break the law and if caught would lose my horses and go to jail. Even if I managed to somehow unload my horses and escape, I’d be a fugitive. But I was almost broke and couldn’t afford to ship my mares any farther.

Back in Guatemala City, a local television station had offered $250.00 to the first person over 2 meters tall who came to claim it. No one did. Though I was above that height I was unaware of the offer until it expired. With that amount added to what I had, I could have continued by train to Mexicali, on the California border.

After one set of officials left and before their replacements arrived, I unloaded my mares and hurried to the nearby Mexico City stockyards. With Hamaca and Ima hidden among cows in a remote corner, I took a series of busses to the Ministry of Agriculture, the very agency that was probably getting ready to order police to find me. There I asked for the national Secretary of Agriculture, provoking disbelieving grins that faded when I showed my letters of recommendation from Secretaries of Agriculture in Costa Rica, Nicaragua, and Guatemala. Mexico’s Secretary extended me a welcome that must have struck his staff as overly cordial for someone dressed as I was. When our meeting was over, I had special permits that allowed my horses and me to cross Mexico by whatever means I chose.

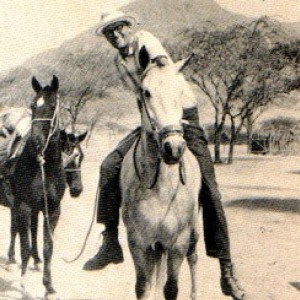

My journey had taken my horses through the Andes, the tropics, and some of the world’s driest deserts. We had traveled part of the way in trains and trucks. We’d passed above bandit-infested Colombia in an antique airplane. But under our own power, we had traveled two thousand miles. And sur vived Peru’s infamous Matacaballo (Horsekiller) desert, which earned its macabre nickname by turning countless horses and more than one man into sun-bleached skeletons. At the thermometer’s other end, we had crossed the Peak of Death, where a group of ill-fated travelers once froze to death in standing positions.

vived Peru’s infamous Matacaballo (Horsekiller) desert, which earned its macabre nickname by turning countless horses and more than one man into sun-bleached skeletons. At the thermometer’s other end, we had crossed the Peak of Death, where a group of ill-fated travelers once froze to death in standing positions.

Central America’s sauna-like heat was unbearable. Locals carried parasols to protect themselves from the sun. Those too poor to afford such luxuries—me for example—used gigantic leaves instead. Beds in cheap hotels came with only a bottom sheet, which was more than sufficient. After other Americans fled a revolution in Nicaragua, my horses and I entered amidst reports that violence was about to break out again. Guns were part of everyday life in El Salvador where signs warned patrons in bars and restaurants: “Check your firearms with the bartender. They will be returned when you leave.”

Before each border, I dealt with bureaucracies that manufactured mountains of paperwork at my expense. Next came corrupt border officials who found fault with that paperwork, hoping for bribes. By the time I left the gigantic Mexico City stockyard, my horses were so accustomed to the unusual that they nonchalantly walked right into two trucks carrying tons of bloody cowhides and were more concerned with being separated. More than once, they followed me inside stores, having slept in the back rooms of such establishments in the Andes.

After leaving Mexico City, I got within four hundred miles of California by hitchhiking rides in cattle trucks. With less than eighteen dollars in my pocket, I had 400 miles to go. I’d learned to make a dollar go a long way, but not that far. A miraculous solution came when I was offered a job as a picador. The pay would be a free train ride for me and my mares to the California border.

There are picadors —courageous mounted men who defy death to joust with brave bulls in front of thousands of spectators—and picadors—dirty, tired men who defy foul odors to care for cattle on railroad trains. I was one of the latter. Problem was, I didn’t have a work permit. My letter of recommendation from Mexico’s Secretary of Agriculture solved that problem.

—courageous mounted men who defy death to joust with brave bulls in front of thousands of spectators—and picadors—dirty, tired men who defy foul odors to care for cattle on railroad trains. I was one of the latter. Problem was, I didn’t have a work permit. My letter of recommendation from Mexico’s Secretary of Agriculture solved that problem.

“With that letter, no one can stop you,” said the man who’d tried to stop me.

A picador’s job is simple. When a cow falls he uses a long prod pole to clear a space so the animal can get back on his feet. Aside from that a picador’s life is boring. But not if two of them squeeze through a small crawl hole, climb an outside ladder, and sit on the boxcar’s roof—eating oranges while enjoying desert scenery.

At night Carlos slept in the caboose and I unrolled my sleeping bag on a ten-and-a-half-inch-wide plank in a boxcar. Done, I looked down at sixty-four dagger-like horns and a hundred twenty-eight hooves supporting fourteen tons of beef. To increase my odds of survival, I wrapped a rope twice around myself and the plank, then tied it. I’d never been more tired but didn’t sleep a wink.

The day after being released from U.S. quarantine I was invited to ride in the grand entry at the Cattle Call horse show, where a camera crew from ABC’s Wide World of Sports filmed me. Then John DeLozier picked me up and my horses up and took me home. My nine-month status as a celebrity was over.

Traveling on horseback I’d seen and experienced things that are missed by an average tourist. My mares and I had journeyed 8,000 miles across 11 nations during the nine most intense months of my life. There were few days when I didn’t see or experience something spectacular, frightening, or unbelievable.

Best of all, my destiny was forever linked to that of the Peruvian Paso breed. I wound up traveling to Peru sixty-five times during the next thirty years—living wonderful adventures and making friends I couldn’t have met any other way. Now I look back on countless memories, most of which make me smile. That—for me at least—is the definition of a life well lived.